Amrita Hepi. Still from The Pace 2018. Co-commissioned by Cement Fondu and The Lock Up. Image courtesy the artist

At some point in all our lives we’ve picked up a skipping rope and jumped over it. Maybe in the playground or in the gym. For play or a serious fitness workout. With a group of friends or on our own. Invariably in time to a musical beat or song.

Busking in Amsterdam August 2016. Image courtesy Jeremy and Leila

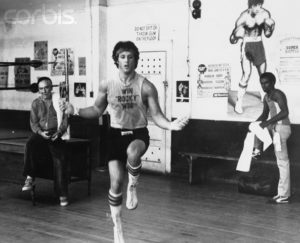

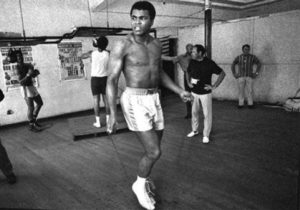

We’ve seen boxers do it in training.

Sylvester Stallone as Rocky Balboa (1979) training for a heavy weight title fight.

Muhammed Ali training with jump rope

Indeed some have taken it a few jumps further, to pursue the international sport of jump rope, competing in timed speed and freestyle events.

Team Azure, Australian team at the 2016 FISAC World Championships Malmo Sweden. Thanks Jeremy, Camryn and Felix

Team Azure, Skipping Australia at the 2016 World Skipping Championships Malmo. Thank you Jeremy, Camryn and Felix

There are few discussions about the cultural significance of jump rope and people still raise their eyebrows when it is introduced to them as a competitive sport – though once they see the athletic prowess required, they don’t question its validity. Fox Sports has been slow to catch on.

Artist Amrita Hepi has shaken up the status quo and taken skipping as far as she can, using the mechanics, the associations and metaphors for skipping and the rope as the basis for her latest work – The Pace.

Hepi is a Bundjulung (Aus) and Ngapuhi (NZ) woman whose evoloving career is on an upward trajectory. Trained and respected as a dancer and choreographer, Hepi’s practice embraces other disciplines – film, performance, sculpture, and public engagement and participation. She uses these to explore her main interests around authenticity, contemporary manifestations of traditional culture and lore, and the politics of race and gender. The connecting thread to all her work remains the body – how movement and dance are conceived from, and then become, the creative expressions of an individual’s or communities’ histories and identities. Embedded in thoughtful gestures and movements, be they spontaneous or well-practised, are a wealth of personal and collective stories.

Amrita Hepi. A Call to Dance 2016. Image courtesy the artist and Performing Lines. Photo credit: Sarah Walker

Amrita Hepi. Image from her performance Caltex Spectrum for the 2018 Keir Choreographic Awards. Winner Audience Choice Award.

The Pace is a 3 channel video installation which uses archival and recent footage of skipping and its quintessential elements – the rope, the jump and the beat – to recognise its broader social and cultural history, and introduce a different symbolism. Whilst we’re held in awe of the physical demands of the jumping, twisting, turning, landing body, as play or serious sport, it is presented by Hepi as another form of choreography – another opportunity for her to use the body and movement as a means to express stories of culture, knowledge and tradition.

Amrita Hepi, The Pace 2018 installation view. Image courtesy the artist. Photo credit: Maria Boyagdis

There are outbursts of great joy and energy, as large and small groups, work to achieve that sublime moment of being truly in sync. There are tougher scenes of political protests meeting with police violence. There is the beautiful meditative moment of the solo dancer, slowly jumping on the cliff top against the backdrop of the sea.

Amrita Hepi still from The Pace 2018. Image courtesy the artist

Says Hepi in the terrific catalogue essay accompanying the exhibition: “In muscles, nerves and flesh, preceding cultural histories are carried forward into the future. It is the body – at pace – that connects divergent narratives and experiences…in a complex web of being human.”

Jump rope can tell us of the histories of young African-American and Indigenous girls. How they played together, jumping in time to chants that spoke of age-old lessons and stories, collectively enjoying the beat and sense of freedom. It was playing outside any codified or structured framework or ritual: it was part of, and became an expression of, everyday life.

Children jumping rope on the pavement of a south side Chicago street. April 1941. Shorpy Historic Picture Archives.

Evanston School children lesson learning. c1900.

Going back further, it references the first Dutch settlers to Northern America who used two ropes to turn and jump through, whilst chanting in a language the British colonists did not understand – hence the double entendre “double dutch”. (If you’re interested to take a more academic dive into this history of jump rope, download the thesis by Wynetta Ann Scott-Simmons Self, Other & Jump Rope Community: The Triumphs of African American Women published by Georgia Southern University in 2007.)

As a relatively little known competitive sport, jump rope tests the physical strength and agility, commitment and a fearlessness to keep beyond the rope at speed, in the air, doing cartwheels or backflips with or without a team member, as it is crossed, turned or flung.

Team Azure, Australian team at the 2016 FISAC World Championships Malmo. Thank you Jeremy, Camryn, Leila and Felix

Interspersed throughout The Pace with imagery of the-jumping-bodies-through-the-turning-ropes are ropes of other kinds: spider’s webs, chains, hair braids, threads for weaving, life lines, safety lines, umbilical cords and intravenous lines. All of which become metaphors for the ties that bind, hold, capture, connect, nourish, tether and weave different life experiences together, as interpreted through the eyes and insights of this young Indigenous female artist.

How long is a piece of string? As far as Hepi wants to take it.

Hepi claims a synergy between the collective activity of turning the rope, be it for sport or play, with that of the weaving traditions of Indigenous women. And to affirm this connection, alongside her video, is an exhibition of beautiful weavings by the Yirran Miigaydhu group (‘many women weavers’), which meets at the Campbelltown Arts Centre each month to weave together. As they weave grasses together, they exchange stories and issues facing their respective communities, connecting to culture and language.

Installation view Yirran Miigaydhu Weavers. Cement Fondu. Image courtesy the artists

Delphine Leslie, Gamilaroi/ Mandandanji Qld. Basket of vine, emu feathers and clay. 2018

The Pace was commissioned by Cement Fondu (Sydney) and The Lock Up (Newcastle) and is now showing in association with Sydney Festival 2019.

The Lock Up is an independent multidisciplinary contemporary arts space in central Newcastle. As its name suggests The Lock Up was a police station which has been transformed into an independent creative hub, featuring artists working across experimental and multidisciplinary art forms. Don’t believe anyone who suggests that if you live outside inner Sydney, you’re missing out! Those days are long gone.

Jen Denzin and Oliver Harlen. Argo Pacifico. On now at The Lock Up, Newcastle

Based in Paddington, Cement Fondu is the phoenix which arose from the closure of Stills Gallery, the contemporary art photography gallery of great note. Since opening in 2018, Cement Fondu has presented an ambitious program of multi-art form exhibitions, performances, public workshops and artist residencies, working with national and international artists. Pairing early career Australian artists with esteemed international artists is an ambitious feature of Cement Fondu’s annual program. The first iteration was Sense, in which French-born, Belgium-based Laure Prouvost’s video work was presented in tandem with a newly commissioned installation and live work by Sydney-based artist Emily Parsons-Lord. Prouvost won the highly prestigious Turner Prize in 2013 and will represent France in the upcoming 2019 Venice Biennale. Cement Fondu’s international reach has serious muscle and brings great energy to the Sydney art scene.

Emily Parsons-Lord X Laure Prouvost 2018. Image courtesy the artists and Cement Fondu

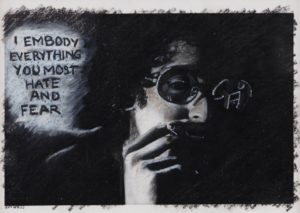

To co-incide with this Sydney Festival is the second iteration of the national/ international pairings at Cement Fondu. Alongside Amrita’s video work are three videos by leading international conceptual artist and philosopher Adrian Piper, which, together, extend the discussion around truth in histories as it pertains to women of colour. Piper’s work reflects her own African-American heritage within a feminist tradition, which she has been pursuing since the late 60s/ early 70s, in her student days in New York. Known for her uncompromising and fiercely independent approach, Piper’s influential work has directly addressed gender, race, xenophobia, and, more recently, social engagement and self-transcendence.

Adrian Piper The Mythic Being: I Embody Everything You Most Hate and Fear 1975, oil crayon on gelatin silver print. Image courtesy Adrian Piper and the APRF, Berlin.

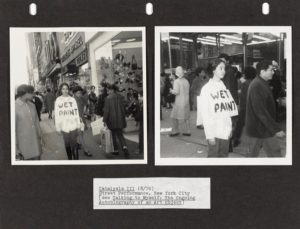

Adrian Piper Catalysis III, 1970 – 73 street performance NYC. Image courtesy the artist and APRF Berlin

Adrian Piper, I am the Locus (#2), 1975, oil crayon drawing on photograph.

Image courtesy the artist and Smart Museum of Art, Uni of Chicago

Piper has an impressive career, including a recent major survey at MOMA in New York in 2018, and Winner of the prestigious Golden Lion Award for Best Artist in 2015 Venice Biennale. The citation for the Golden Lion Award reads: “Piper has reformed conceptual practice to include personal subjectivity—of herself, her audience and the publics in general. Her presentations invite us to engage in a life-long performance of personal responsibility and call our attention to the ephemeral and transitional character of value systems.”

Adrian Piper with the Golden Lion Award for Best Artist at the 2015 Venice Biennale

Though Piper has exhibited in Australia before, in a collaborative project with Brenda L. Croft, Gurindji/Malngin/Mudpurra artist, curator and academic, in the 9th Biennale of Sydney: The Boundary Rider curated by Tony Bond, I imagine it is nonetheless quite a coup for these local commissioning galleries to present her work.

Her work in Sydney currently includes three older videos all of which, though seemingly documentary in style, possess a deeply thoughtful and personal honesty. There is great emotion in these works which is perhaps not the response much conceptual art seeks.

Presented as a silent disco – a fab current fad where everyone wears headphones with a selection of different music tracks from which to choose, then dances solo and in overall silence – you put on your headphones, click to the soundtrack associated with the video, and watch and listen and be moved – emotionally and physically.

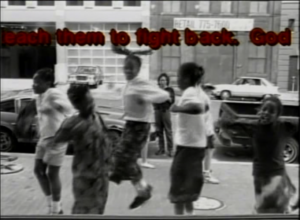

The poignancy of the moving video Please, God from 1991 in which your heart swells with the sheer joy of watching young African-American girls innocently dance in front of a shop window, obviously watching something on a display TV. You feel the age of the times – the fashion, the cars driving past, it’s in B&W – and the darkness of the times: with overlaid scrolling text as simple prayers starting with “Please, God….”, as a glimpse into a future of discrimination these gorgeous happy girls will come up against.

Adrian Piper stills from Please God 1991. Image courtesy the artist and the APRF Berlin

Adrian Moves to Berlin (and she does live in Berlin) is more recent and is an hour of Adrian dancing continuously and alone, to music, in AlexanderPlatz in Berlin. She eschews a wonderful sense of freedom by just moving to the groove in public, on her own, with confidence and intent, and without stopping. Piper is interested in how dance can be both about protest and celebration. She found that, following the collapse of the Berlin Wall, people sought new ways in which to come together as a united community – dance was one of the ways.

Adrian Piper Adrian moves to Berlin 2007, still from video. Image courtesy the artist and the APRF Berlin

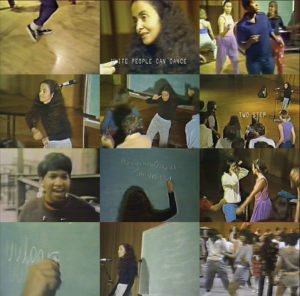

Then head on upstairs with your headphones to watch what is probably Piper’s most well-known of videos: Funk Lessons (1983-84) in which Piper is filmed giving ‘funk’ history classes to a group of students at UC Berkeley – though with an agenda. She asks of the students to listen and dance to funk music. In so doing, she is asking them to think about the origins of funk music and who may be the true champions of a style of music which had a massive and enduring influence on culture and music throughout the 20th century. Are these champions household names? Or was it their followers who were picked up and promoted by the mainstream white impresarios?

Adrian Piper still from Funk Lessons 1983. Image courtesy the artist and the APRF Berlin

Twelve stills from Adrian Piper’s Funk Lessons, 1983–84, video, color, sound, 15 minutes 17 seconds. Video: Sam Samore. Image courtesy the artist and APRF Berlin

There are many threads in this paired exhibition, connecting the practices of these two women. The video format works really well: enjoy the luxury of watching each gesture, stance or jump, over and over, to absorb every nuance and subtlety. Both have filmed and presented epic dances, choreographed from everyday life, which are celebratory, provocative, emotional, optimistic and, above all, meaningful.

Image from Newark Happening.com

Jump to it! It’s a must see. Cement Fondu 36 Gosbell St Paddington. On until 24 February 2019.

No Comments Yet