Looking towards Hanalei Bay, Kauai Hawaii

You may hear Aloha and think leis, mai tais and Waikiki.

But, as I have recently discovered, there is much more to the city of Honolulu, indeed the islands of Hawaii, than the obvious clichés. There is art to be had, of a calibre and richness that is both inspirational and enjoyable.

On Diamond Head, a fairly well-to-do neighbourhood 25 minutes drive east of Waikiki, is the only public museum in the USA wholly dedicated to the study and understanding of Islamic arts and cultures: the private home turned public museum Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture and Design.

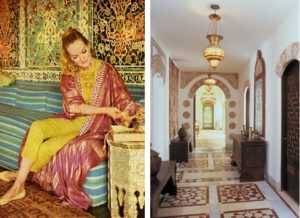

Doris Duke, with her Middle-Eastern jewelry in a box on top of a Syrian tabouret inlaid with mother-of-pearl, Vogue 1966 and a marble paved hallway

Doris Duke’s Shangri La is a treasure trove. The story behind it is as glamorous as can be expected from an American heir to a tobacco fortune. Shangri La was built by Doris Duke between 1930 -36 and is considered one of Hawaii’s most architecturally significant homes. The name Shangri La is apt, conjuring a fantastical private retreat of great beauty and wonder, on a level that only vast amounts of money can create. The collection it houses is acknowledged as one of great international importance.

Over 60 years, Duke amassed a collection of about 2,500 objects, many of which are embedded into the structure of the house. Iranian ceramic tile panels, carved and painted ceilings from Morocco, jalis (perforated screens) doors and windows, and textiles and carpets creating a living environment of Islamic art and architectural decoration. Her interest in Islamic culture ran deep such that she established a foundation – the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art (DDFIA) – specifically to promote the study and understanding of Islamic arts and cultures via the management and preservation of the Shangri La. Interestingly the DDFIA also manages the Building Bridges Program (based in New York) to support the use of arts and media to enhance Americans’ understanding of Muslim societies.

Though the origin of the Shangri La is shaped by the woman who created it, the DDFIA is ambitious to extend the narrative. Its collection, its artist-in-residence program and guided tours can play a leading role in strengthening a wider appreciation and understanding for the depth, breadth, sophistication and breath-taking beauty of Islamic culture and its arts and artefacts.

Duke described her home as a mix of Spanish Moorish Persian Indian influences

The DDFIA has managed the shift from private home to public museum, engaging museum professionals; funding extensive and ongoing conservation of artworks, artefacts, the gardens, pool and structure itself, as well as the development of public education programs. So it is only relatively recently, that the Shangri La has been ready to be experienced in all its glory, by an inquiring public. Though to control numbers and ensure safety of the home, visits by the public are managed in small group tours, to be booked in advance. Check out the site for more info.

Shangri La living room

Reception room. Syrian, late Ottoman

Shangri La Dining Room

Shangri La Damascene room.Syria late 18thC

Bahia Shebab My People 2018. Acrylic & latex on wood. Artist in Residence Shangri La, Honolulu.

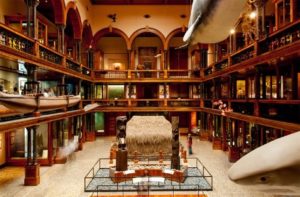

Back in downtown Honolulu, there is the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, a volcanic stone pile in the Scottish tradition. Again, it has an extraordinary story behind its origins. Founded by Charles Reed Bishop in 1889, it was to honour the memory of his late wife, Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop, the last descendant of the royal Kamehameha family.

Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop (1831-1884)

The Bishop Museum, Honolulu

Permanent exhibition display in The Bishop Museum

The Museum was established initially to house the extensive collection of Hawaiian objects and royal family heirlooms of the Princess. It expanded to include more examples of Hawaiian and other Pacific Islands’ histories and cultures and now houses over 25million historical, cultural and national treasures from around the Pacific. Plan your trip, take your time and soak in the wonder and diversity of the handicrafts grouped in displays, which were the tools, transport, housing, adornments, clothing and food sources of the Hawaiians, Polynesians, Melanesians, Micronesians of the Pacific Islands.

Hawaiian Hall. Bishop Museum, Honolulu

But the timing for my visit was to experience something more contemporary and conceptual, the Honolulu Biennial an event which focuses on artists from Hawaii and the countries and continents united by the Pacific Ocean.

Nicholas Galanin We dreamt deaf 2015, taxidermied polar bear. Exhibited at the Honolulu Museum of Art. Honolulu Biennial 2019.

Chiharu Shiota Crossroads 2019 (detail). wool, maps, staples. Exhibited at The Hub. Honolulu Biennial 2019

The Biennial began in 2017 so this, in March 2019, is only the second of its curated presentations. It shines an inquiring and bright light on an active and sophisticated local contemporary art scene.

There are many biennials, biennales and triennales these days. So why another one and why Hawaii? Because, as the founders say, contemporary Hawaiian and local artists from Hawaii have been underrepresented in the international contemporary art circuit. That has shifted since the Biennial’s inception in 2017.

The Biennial didn’t just happen in a vacuum. It was a clear strategy devised by the three Founders – two international curators and one business manager, all with strong links to Hawaii – to establish a major recurring art event which was connected to the local art scene and community, which could ably and intelligently support and promote Hawaiian artists within a broader international context, in dialogue with international artists, curators, collectors and influencers.

As early as 2014, the founders began a program of exhibiting work in a range of different spaces – warehouses, disused retail – which was ambitious in scale and concept. The pre-Biennial program was intended to stretch local artists, arts and business communities, and the general public, to recognise that a locally-owned and directed art event was possible, had potential and could be inspiring and exciting. It is now round 2 and the event is well worth adding to the art travel calendar.

The curatorial premise of the 2019 Biennial is embedded in a traditional and particularly significant Native Hawaiian practice known as ‘aha- sennit or cordage. Its focus is on the Pacific and theme emphasises genealogical ties within the region and issues specific to it.

Cordage is many strands of plant fibre gathered together, making a strong cable for use as clothing, shelter, ritual ceremony and canoes. The most common and best quality of the cordages is ‘aha (sennit) which comes from coconut fibre and is regarded for its thickness and relative water resistance.

As an integral part of traditional life, cordage became more than a physical lifeline, it came to represent metaphysical concepts, including those of spiritual connections between ancestors and present generations as embodied in the umbilical cord.

It required great skill to make cordage that was durable and strong and, with increased Western influences and demands, the collective capacity to create cordage and retain its spiritual connections, were fading. It is only in relatively recent times, that a focus has been brought back to the practice, to ensure it continues.

The message from the Biennial as described in its title – “To Make Wrong/ Right/ Now” – is drawn from the poem by Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) artist Imaikalani Kalahele.

The source of my origins lie beneath my feet,

the breath in my chest originated in Pō

the destiny of my race is plunged into my gut and infesting my veins

with a new nationalism, old spiritualism, and a need to make wrong right now.

— Imaikalani Kalahele, “Manifesto” from Kalahele (Honolulu: Kalamakū Press)

Together with the title proclamation, the Biennial encourages participating artists to ‘knot’ together traditional concepts of ‘aha – sennit with contemporary perspectives, to weave stories of past and present generations, to reclaim of traditional knowledge and practices, to gather, remember, share, learn and move forward together in this place.

There is a similar conversation happening in Hawaii as here in Australia: a reclamation of Indigenous voices; a reconsideration of the status quo; a reaffirmation of Indigenous knowledge, leadership and culture. The messaging from Native Hawaiian artists echoes that of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists: eloquent, potent and direct statements which are as much about opening eyes and minds to prevailing prejudices and injustices, as they are a call to action and to make wrong right.

My first encounter of contemporary Hawaiian art was an installation of new ritual cord garments made by teacher, hula dancer and Director of Hawaiian Culture and Protocols Engagement at the University of Hawaii, Dr Taupouri Tangaro. Though based in tradition, the regalia resemble couture fashion. His academic practice is based on knotting cord items, including ritual garments, as a means by which to further Indigenous leadership and knowledge.

Taupōuri Tangarō Installation view at the Honolulu Biennial 2019 Hub. Courtesy of the Honolulu Biennial Foundation. Photo by Christopher Rohrer

Taupōuri Tangarō

Huihui Pāʻū (Constellated Pāʻū), 2018. Cotton cord, kauila wood (carved image by Ronald Kanakanui, Puna, Hawaii).

Installed at the Honolulu Biennial 2019 Hub.

Courtesy of the Honolulu Biennial Foundation. Photo by Christopher Rohrer.

Tangaro worked with a small community on an outer lying island which still uses traditional and highly revered knotting techniques to fashion garments such as cord skirts and shoulder regalia designed to accommodate traditional dance movements, to be worn low and wide; and ritual sashes with dog teeth decorations (dogs were used for food and as a lucky charm in traditional Hawaii until native religion was abandoned). Another is a nod to contemporary Hawaii and is styled on an Opera cloak and knotted in cotton cord.

Tangaro’s collection would add well to that of The Bishop Museum. I understand The Bishop has only one historic ritual corded skirt in its vast collection of artefacts (and which was in storage and unavailable for viewing when I was there). Tangaro’s research, dance and garment-making practice seeks a relevance for tradition in modern life and a way in which to preserve language and culture.

Here is a fabulous youtube clip of Tangaro leading a traditional hula concert at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival in 2012. Lengthy but well worth watching.

The Honolulu Museum of Art was one of the many venues for the Biennial with several major installations, including one by Native Hawaiian artist Kapolani Landgraf.

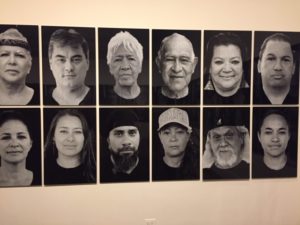

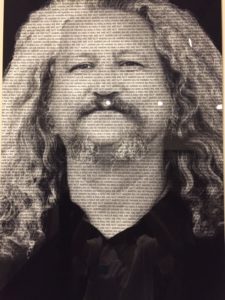

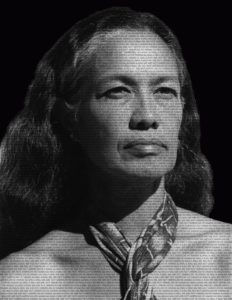

Kapulani Landgraf’s photographic installation ‘Au’a, Ka-elo is a compelling installation of 100 B&W portraits each with fine text repeatedly overlaid on each face, citing “I am not American – HE HAWAII AU MAU A MAU”, which translates as “I am Hawaiian for ever and ever”. This phrase was chanted by leading poet and activist Haunani-Kay Trask at the 1993 public observance of the centenary of the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy. It was a powerful phrase picked up by the 10,000 or so people in attendance and has become an enduring mantra of the sovereignty movement in Hawaii.

Each portrait comprising the installation is that of a Native Hawaiian Kapolani respects as a leader, all of whom contribute to contemporary Hawaiian social, cultural, political and business life. Landgraf has captured a collective strength, warmth and pride in those who head her community, particularly of Hanuani who is photographed, as is Kalahele, whose poem underscores the theme of the Biennial.

Kapulani Landgraf Au’a, Ka’elo 2019 (detail) digital metal prints. Exhibited at the Honolulu Museum of Art. Honolulu Biennial 2019

People who took participated in ʻ‘Au‘a visited the installation on March 9 2019

Kapulani Landgraf. Au’a Ka’elo 2019 – portrait of poet Imaikalani Kalahele. Honolulu Biennial 2019

Kapulani Landgraf. Au’a Ka’elo 2019 – portrait of poet activist Dr Hanuani-Kay Trask Honolulu Biennial 2019

Other photographs by Landgraf are featured in the current Asia-Pacific Triennial at QAGOMA

Participating local sculptor Leland Miyano won the inaugural Golden Hibiscus Award for his life-size traditional double-hull Polynesian canoe Hauka’i/ A Wake , installed in the Foster Botanical Garden. Though known more for his stone work, Miyano collected fallen branches and vines from non-native trees to weave and plait the canoe, with the help of many in the community.

Leland Miyano Hauka’i/ A Wake 2019 found and invasive botanical materials (detail). Honolulu Biennial 2019

Leland Miyano Hauka’i/ A Wake 2019 found and invasive botanical materials (detail). Honolulu Biennial 2019

Commissioned for this Biennial, the work highlights Miyano’s concerns for the local environment, as well as his respect for his intrepid Hawaiian ancestors who voyaged around the Polynesian islands. A Wake is the flow of water behind the canoes; the celebration of life, as well as an awakened state, alert to what is going on around us.

Intriguing is the woven pandanus 2D screen framing an asymmetrical grid of shapes (and the title of the work), which replicates the ‘compass’ used by the Hawaiian voyagers to navigate their way across the Pacific.

Lelan Miyano Hauka’i/A Wake 2019 – based on a traditional navigational grid (detail). Installed in the Foster Botanical Gardens. Honolulu Biennial 2019

Hawaii-based artist Bernice Akamine positioned her simple installations at various sites around Honolulu. Houselessness, is a simple tent-like shelter, with the Hawaiian flag as the cover and woven cardboard inside on the ground as the sleeping mat.

Bernice Akamine Houselessness 2019 tent and sleeping mat. Flag and cardboard. Honolulu Biennial 2019

The flag – a design incorporating the Union Jack and the stripes of the USA flag – is hard to miss as are the many who exist on the streets and in the parks, across Honolulu. It is a beautiful city, a sought-after tourist destination, yet is grappling with the crisis of houselessness. To me that signifies the lack of shelter, temporary or otherwise, including places which could be called home, for the many people on the streets.

The Hawaiian flag confounded us, though it shouldn’t have really given that it seems to share similar issues to that which signifies Australia. Both remain an acknowledgement of a colonial past with no mark of Indigenous representation.

Filipino American artist Paul Pfeiffer presented two major installations, one the highly regarded video installation Three Figures in a Room from 2015 and the other, a new site-specific installation Poltergeist for the Bishop Museum. Both are in keeping with his approach of recasting images of popular spectacles or myths to shift perceptions of ourselves and our world.

Paul Pfeiffer Poltergeist 2019 installation detail. Exhibited at The Bishop Museum for the Honolulu Biennial 2019

Poltergeist pays a homage to the memory of Prince Albert Kaleiopapa a Kamehameha, the much-loved only child of Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma who died at the age of 4, leaving the monarchy without an heir. He was born in 1858, the first child to be born to a reigning Hawaiian monarch since 1839, and the last ever to be born to any reigning Hawaiian monarch. His brief life and early death had a profound effect on the Hawaiian monarchy and was deeply felt by the community. Pfeiffer’s installation of ready-made sculptures and historical documents and photographs elaborate on the stories and myths around the young child at the centre of extraordinary historical times.

You may remember Pfeiffer’s work here in Australia at both the NGV in 2005-06 and in the Biennale of Sydney in 2008.

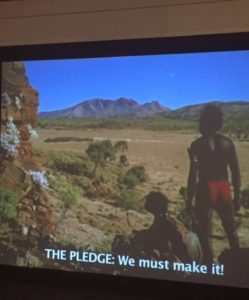

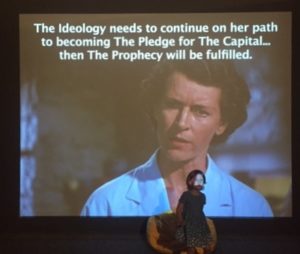

Australia was ably-represented by two artists of great esteem whose practices sit well within the exhibition narrative: Brook Andrew with his 2011 film The Pledge, a rescripted revision of Charles Chauvel’s film Jedda with a sci-fi twist, and Taloi Havini’s 3-channel video installation Habitat II, which takes us slowly through the environmental devastation left behind by the Panguna Copper Mine in Bougainville. It is as gut-wrenching as when I first saw it in 2017 in the AGNSW, when exhibited as a new acquisition.

Taloi Havini Habitat 2017 3 channel video (detail). Images courtesy the artist and AGNSW. Exhibited at The Hub, Honolulu Biennial 2019

Brook Andrew The Pledge 2011 video installation (detail). Images courtesy the artist. Exhibited at The Hub, Honolulu Biennial 2019

Though Hawaii thrives on tourism, little of it has been focussed on a deep engagement with local indigenous culture. By all means, enjoy the shopping, surfing and slurping colourful coconut cocktails with umbrellas in them. I surfed at Waikiki, shopped at the Ala Moana Centre and kept my myself nice with just one Blue Hawaiian at the Lava Tube night club.

But what should not be bypassed is the museum/ gallery experience in Honolulu.

Generally (apparently) tourists in search of a vibrant cultural experience have a greater economic impact and make more meaningful connections with a place as they tend to linger longer, have extended conversations with individuals and absorb a more considered awareness of locale, history, culture and people. Look at the economic impact of MONA in Tasmania, bolstering tourism, employment and industry for the island state which successive Governments have never been able to achieve. Or how much of a game-changer Judith Nielsen’s collection, White Rabbit Gallery, Dangrove and soon to open performance space Phoenix projects have been for central Sydney.

Experiencing local art within a wider context, chatting with artists, and learning more about the history and stories of Hawaii has left a deep impression and has been a memorable and invigorating introduction to this beautiful suite of islands.

Mahalo!

2 Comments

Great read thanks Fiona. The Honolulu Biennial is on the list for 2021! Maholo

Wow Fiona what a fantastic trip, amazing places to see & learn from. Never thought I wanted to go to Hawaii but now I do, thank you. Gabrielle